This blog post talks about one of many aspects of trauma that is often forgotten: the context of our lives and how that impacts our experience of trauma.

Trauma is at the heart of much of what we think of as ‘mental illness’

I write a lot about trauma on this blog. That’s because one of the most important things I learned during my healing was that none of the psychiatric labels, medications or ECT I was given dealt with the fundamental issue at the heart of my distress: trauma.

Yes, I heard voices, I had unusual beliefs. Yes, I self-harmed and attempted suicide. But while psychiatry sees those experiences as signs of illness, for me they were something much more human. They were a normal response to some very extreme, traumatic experiences.

In my early childhood I experienced neglect and physical violence from my primary caregiver. And at the age of 13, after running away from home, I was abducted and sexually assaulted. The shame I felt, particularly about the sexual assault, was devastating. Yet, despite nine years as a mental health consumer, not one worker ever asked me about trauma.

What do we mean by trauma?

Lots of people struggle to get their head around what trauma means. I think that can be true whether we’re a survivor, a loved one or in a helping role.

As survivors, often we don’t think of our experience as trauma. I know that I didn’t. For many years I didn’t even use words like sexual assault, rape or abuse. Instead, I used to think about ‘that thing that happened when I was thirteen’.

You can find lots of different definitions for trauma on the internet and in academic journals. One of the most commonly used definitions is this one, by SAMHSA:

Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening with lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.

Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), US

It’s not a bad definition, but it doesn’t fully connect with my lived experience.

Trauma is an experience, not an event

When I think about my own trauma, and the many survivors I’ve worked with over the years, our stories are often so much about actual traumatic events, but far more about the personal experience.

These are the elements that seem to almost universally define trauma:

- Overwhelming experience/s, feeling powerless

- Threatened, direct or indirect harm (i.e, harm to self or witnessing harm to others, including physical, emotional, mental, cultural, social and spiritual harms)

- Extreme emotional impacts including fear/terror, shame, despair and anger

- Profound impacts on self-identity and worldview

Thinking about trauma in this way aligns with the Power Threat Meaning Framework (British Psychological Society). This framework can be a useful way of exploring trauma which aligns with lived experience.

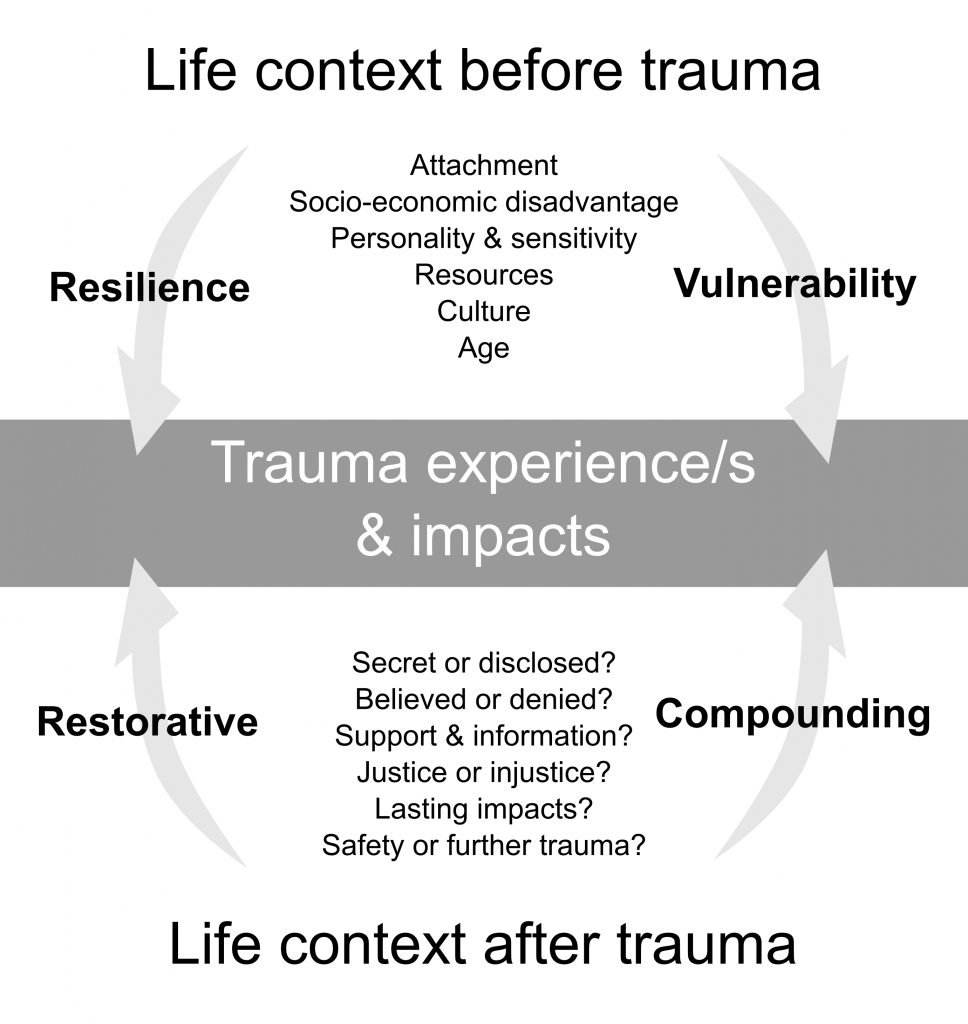

Trauma occurs in a context, and that affects our experience

Lots of people have asked me why trauma affected them so badly, when others with a similar experience seem fine. Some clinicians have asked me about the same thing. And this raises an important, yet often overlooked, aspect of trauma: the context in which it happens.

I have no doubt, that regardless of the context, my own experience of sexual violence would have been traumatic. But would it have had the same impact in a different context to my own?

Before the trauma: Resilience or vulnerability?

Before I experienced the abduction and rape, my life context did not set me up to have much in the way of resilience. And resilience, of course, is not something we achieve, but rather a consequence of the social determinants that life has dealt us. Instead, I was probably more vulnerable than others. For example:

- I had already experienced neglect and physical violence at home and bullying at school. These things were already shaping my identity and sense of the world.

- I grew up with a single mother on a mostly low income, we often struggled for the basics.

- We moved to a new house at least every year, sometimes more, and I changed schools and neighbourhoods a lot. This made it hard to keep friends and have confidants.

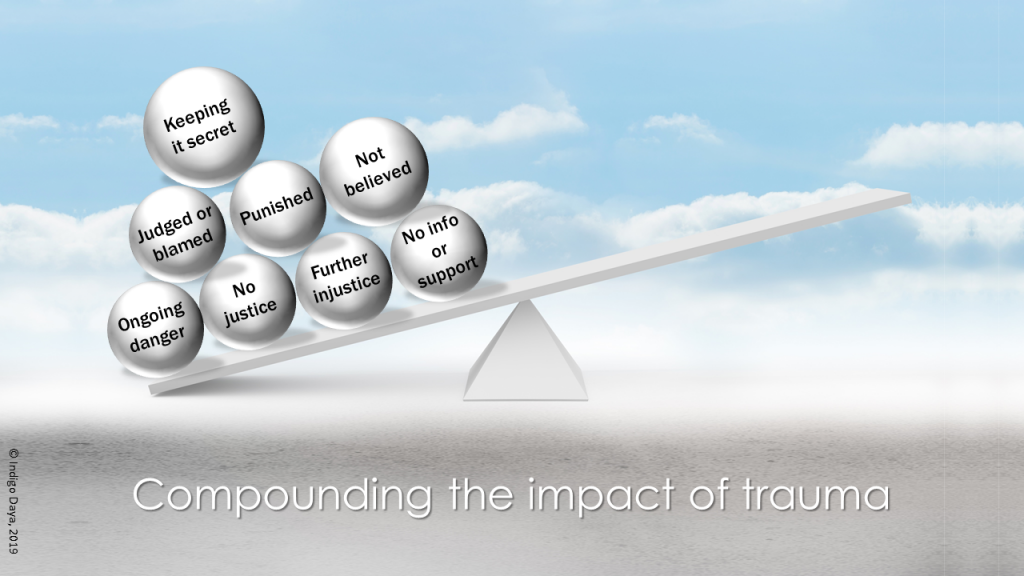

After trauma: Compounding or restorative impacts?

After the abduction and rape, the things that happened in my life context compounded the impact of trauma, rather than have a healing or restorative impact. For example:

- Keeping secrets: When I saw my mother again after the abduction, she said she didn’t want to know what happened, and that we should never speak about it again.

- Judged and punished: I was assigned a social worker who told me I was lucky not to have been put in a girls’ home for running away from home.

- No support: because no-one talked about what happened, I received no support, counselling, or even information about sexual violence.

- No justice: The man who abducted and assaulted me was not charged with any crimes.

It was not until 27 years after the trauma that I would finally be able to explore what happened with a trauma therapist. Unfortunately, I had to go against the recommendations of my psychiatrist to do that (read more).

In this therapy, aged forty, for the first time in my life:

- I learned about grooming and Stockholm syndrome, and I was able to start making sense of my feelings about what happened.

- I was offered the chance to pursue justice. Another person thought I was deserving of this.

- Another human being hard my story with deep compassion, and told me that it wasn’t my fault, there was nothing to feel ashamed about.

- I realised that all my so-called ‘mental illness’ was not a meaningless disease, but was actually excruciatingly overblown shame. And that shame was from the trauma.

And it was during this therapy I realised that the secrets, judgement and punishment that came after the trauma, all served to reinforce the feelings of shame. And the lack of support and justice confirmed that I was not worthy of help. The context contributed to my intense feelings of shame about what happened.

But just imagine if my life context had been different. If I had been raised with greater advantages and resources, and to believe that I was a strong and worthy person. And just imagine if, after this terrible trauma happened, that I was asked what happened, provided with care and support, information about the impacts of sexual violence, space, time and encouragement to heal. Imagine if the perpetrator had been charged and convicted and I had seen justice done, with my Mum standing by my side in support.

If all those things had happened, I am sure I would still have been hurt by trauma. But, possibly, the impacts would not have been so severe and enduring that, 27 years later, I was so tormented that I heard voices and wanted to die.

Context matters

My healing, like everyone’s, was complex and time-consuming. You can read more about it in other blog posts. But an important learning was that the context within which my trauma occurred was a big part of how and why it impacted me.

I have seen the impact of context over and over again in the lives of other survivors. I cannot count how many times I have worked with women who were abused by their father, but the bigger issue for them was that their mother didn’t believe them or didn’t help them. I often wonder if it might be true that, while trauma hurts us, it is the lack of care and compassion that comes after that pushes us over the edge.

The model shown below is my attempt to explain some of the key factors in our life context which help to explain why trauma impacts people so differently.

The contextual factors outlined in this model come largely from lived experience stories, but many of these factors are also noted in academic literature. Morrison, Quadara & Boyd (2007) discuss some of these impacts in relation to sexual assaults.

If you’re a survivor of trauma, it can be helpful to know that what happened before and after trauma may be an important part of making sense of your experience. If you’re a supporter or worker, remember to explore people’s broader life context in relation to trauma – this context may hold important clues for recovery and healing.

Comments