This article is a reflection on my first experiences of madness and my first stay in a psychiatric hospital.

A first admission to a psychiatric ward is a startling experience. I am not sure that anyone ever expects to end up in the ‘looney bin’. Certainly I didn’t. This is a place reserved for other people, for properly crazy people.

… As it turned out, most of my fellow patients were far removed from stereotypical nutters themselves. We crazy folks have many experiences and talents, but none of them sufficient to keep us out of the ward. I was to meet mathematicians, artists, musicians, an admiral, and several versions of Jesus.

My beginnings of madness.

I don’t know when I first went mad.

I was anxious in grade one, was that the beginning? What about when I tried to overdose on paracetamol at thirteen, was that madness? What about when I was 22, couldn’t stop my mind racing and found it hard to sleep? Or when I was 26, struggled with existential questions and contemplated stepping in front of trucks when I crossed the road?

At none of these times was I diagnosed with anything, and at all of these times I managed to keep going. Were these precursors of the madness to come, or just normal growing pains?

All my life I’ve been sensitive to sadness and frightened of anger. I’ve felt torn, usually between a need for responsibility, acceptance and achievement – and a burning urge to rebel. At the same time I’ve always been a deep thinker, not necessarily with any genius conclusions to report, I’m sad to say, but certainly I have spent much of my spare time in perplexing (and perhaps egotistical) self-analysis. And I’ve always had a creative side that has taken me in unusual directions.

Are these the ingredients of madness? Or just terribly mundane aspects of being a human being? Again, I really have no idea. All I can do is share my story and let it tell itself.

Emptiness, falling and disappearing.

Blankness.

(journal entry, undated)

Blackness.

Bleakness.

Broken.

Borrowed ideas.

I often talk about how I felt a deep emptiness. I think this was one of my first signs of madness because it overwhelmed me, it made it difficult to keep going. It was excessively persistent and very physical.

I’d had the empty feeling for years. I recall one night, aged 21, when I lay awake all night unable to sleep because I felt like the emptiness in my gut was going to consume me whole. It was terrifying. But then it went, came back for a spell, then left again. For years it was there, beneath the surface.

One day it just came and didn’t leave.

I was almost thirty. This was around the time that I had walked away from my big corporate career in search of happiness or at least peace, and I was studying an art course at a technical college in South Melbourne. I had my own art studio. It was brilliant, just like I’d always imagined.

A kooky, high-ceilinged small space that had been walled off in the corner of a turn-of-the-century building. Painted white, but scruffy with the scratchings of art students who had come before me. It screamed for creation and brilliance. And I recall sitting in the middle of this room, such an opportunity laid out before me, and thinking. Thinking more than I had ever given myself time for.

Forget paint. Space and time are the main ingredients with which we create, and they are plentiful for the art student.

‘Look to yourself for inspiration,’ suggested an art teacher, and so I did. And I found nothing. A vast inner landscape of emptiness. It stretched out and out and out and it was hard to orient myself within it.

I began to paint holes, abysses, voids. I tried to capture the feeling of never-ending space within the confines of canvases. I used layers of translucent colours thinned with glistening oil. Dark, rich colours like alizarin crimson and phthalocyanine green. Intensely vibrant on their own, but when brought together these colours would cancel each other out and create a richer, darker black than any tube of black paint could ever make.

It was the blackness of my life. The paintings didn’t make the emptiness go away, but I did feel slightly satisfied for being able to express it. Imagery was always so much more accurate for me as a language.

Something else that began to plague me was the feeling of falling. You know the feeling. In the pit of your stomach, just as you realise you’ve tripped, but before you hit the ground. Sometimes I get that feeling when a lift gives an unexpected lurch. So imagine that, but sustained for hours on end. It was probably fear.

It made me want to run and hide. But how could I run to a place where I wouldn’t be? How could I hide from myself? Overindulgence in drinking, eating or smoking joints was a common relief for that falling feeling. Sleep, too, if I could manage it.

I used to wish I could organise a coma as a break from myself. I remember asking a psychiatrist years after being diagnosed, quite seriously, if there was any way to voluntarily go into a coma for some respite. He didn’t answer but he did make some notes in my file.

Getting my first label.

I first saw a psychologist in 1999 to get some advice about my partner who was struggling with her own anxieties (we were breaking up but I was worried about her). By the end of an hour I was completing some kind of psychiatric assessment questionnaire. And a couple of hours after that I had a diagnosis myself.

Apparently it wasn’t normal to cover the floor with plastic bags each night so I could hear if anyone was coming to kill me. It also wasn’t normal to wish I was dead, or to cut into my stomach, which I had been increasingly doing in secret. It wasn’t normal to drive to McDonalds to use the toilet, even in the middle of the night, because I was scared of my own toilet and what might happen if I went in there. It wasn’t normal to stare into space for hours and lose touch with reality, or to feel like my insides were eating me alive. It wasn’t normal to decorate the world around me, and my body, with question marks. Or to try to create my own, apparently bizarre, philosophy of meaning.

I was not normal. I had depression. It was an imbalance in my brain chemistry, I was told, kindly. Not my fault. It was an illness. And so I was prescribed antidepressants, and shortly afterwards, mood stabilisers.

It was a shock, but a shock of a manageable nature; depression was, after all, something that movie stars struggled with, and even sports stars and politicians sometimes ‘came out’ with stories of their depression or anxiety in heart-warming inspirational features in women’s magazines.

It made me wonder if this was why I was an artist, and why I liked Nick Cave, Bjork and the bands Radiohead and Portishead so much. While it was scary, it wasn’t terrifying. I took my pills. I still held hope and, strangely, relief. If I was nuts, then I was not responsible for anything I thought or felt or did. I had no control, I would surrender to the system and the professionals would fix me.

But within a relatively short space of time the fear factor began to escalate. A few months after being diagnosed with depression I was suddenly a patient in a psychiatric ward, being told I was suicidal, psychotic, unable to make my own decisions, doped out of my brain on heavy antipsychotic medication, and stunned that I could have ended up in such a place.

This was definitely not the kind of thing movie stars talked about in glossy magazines. This was scary shit. This was foreign and frightening.

Life in a psychiatric ward.

But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat,

“we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, or you wouldn’t have come here.

I can’t remember how I arrived at the hospital that first time. Many of my memories from the early years of madness are jumbled together. I think it’s a combination of medication, shock treatments and extreme emotions. I can never know for sure. But I find it strange that I have lost this particular memory. It was the heralding of my new life as an officially mad person, but somehow I missed the welcome ceremony.

I do remember my first experience on the ward, however, as a nurse seated me at a round, melamine table, with chairs for six people, and asked me to wait while she got paperwork.

The table was clean but slightly worn, a pale lifeless grey, and was a part of the simple dining area – grey, melamine clouds on the horizon of my new world. Except for me the dining area was empty; most of the patients were sitting in front of the television on the other side of a partitioned wall or, as I was to find out later, smoking in the courtyard and chewing over the menu of ward conversation: bitching about staff, competing over medication dosages, trading items of value, sharing stories of outrage, supporting each other, explaining how to get by on the ward or debating the finer points of existential philosophy and spirituality.

That dining space reminded me of childhood visits to the Myers cafeteria in the city with my grandmother. The Myers cafeteria had a character all of its own, embodied by the careful navigation of a speckled brown plastic tray along a stainless steel winding road through glass cabinets. Perfectly cut sandwiches that were tightly ‘plastic-wrapped’ to plates, huge lumps of roast meats glistening in bain maries, apple pie slices sitting jauntily in little white bowls, and a grey-haired lady with a white apron and cash register at the end of the journey. These memories are comforting.

When we went to Myers, my grandmother would treat me to a bowl of jelly with piped cream. It wasn’t until years later my mother enlightened me that my grandmother was a chronic shoplifter who used me as a distraction. Ignorance may not always be bliss, but in my case ignorance was jelly and cream, and that’s OK when you’re a kid. Sometimes even when you’re a grown-up.

The familiar nature of the psych ward dining room to childhood memories gave me a context to make sense of where I was—an institution with structures—but the familiarity ended there.

To my left was a serving counter with a closed and locked roller door, to my right was an empty desk in front of a glass-boxed staff office. The ‘fish bowl’, as we inmates like to call it.

The glass gives staff ‘protection’ and separation from patients, while still allowing them to watch over us. It is never quite clear ‘who’ is in the fish bowl in this situation: the watched do a fair bit of watching themselves.

I could vaguely make out an area on the other side of the office, with patients shuffling about, but tried not to notice; it looked scary. Behind me was an art room, with a few people in wrinkled mint-green pyjamas hunched over paintings on thin paper that curled as the paint dried. Music leaked out through the open art-room door: ‘I feel good; I knew that I would now. I feel good; I knew that I would now. So good! So good! I got you!’

I was alarmed at hearing James Brown’s classic ‘feel good’ song. ‘Please, please, please,’ I begged the universe, ‘don’t let them play happy music here.’

Luckily it was only the radio, a freak moment that took me straight to memories of the maddening music that was played in the day room of ‘One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest’.

In the way of institutions I had known, jelly (or jello for those in the US) was also a fixture at the psych ward dining room. A brightly coloured, wobbly way to mark the passing of time. After a main meal one could choose from a jelly cup (in plastic), an ice cream cup (in cardboard), or the dessert of the day (in a proper bowl).

I had many passionate and well-crafted debates with the dining room lady about needing to eat my jelly with ice cream, rather than instead of ice cream. Jelly and ice-cream, or jelly and cream, I explained, were two sides of the same coin. Without either one you have nothing of value.

By about my third admission to hospital I won this debate, and she would secretly sneak me a tub of each treasured treat at the end of meals. The same dining lady was employed during almost all of my hospital admissions. I think her name was Mary, and I feel saddened that I don’t remember for sure. She was always a friendly face that greeted us from behind that little window, shared a bit of gossip, and seemed not in the least bit concerned that we were often barking mad and messy eaters.

I don’t know why the jelly and ice cream memory is so strong, given all the other extraordinary things that happen in a psych ward. But I suspect it’s because this was an anchoring memory. And perhaps also because this small battle over jelly was a tiny way in which I could take control of what was happening to me.

A first admission to a psychiatric ward is a startling experience. I am not sure that anyone ever expects to end up in the ‘looney bin’. Certainly I didn’t. This is a place reserved for other people, for properly crazy people. It’s a movie set for drama and horror. It’s unreal, unexpected and unknown. Steeped in stereotypes and judgements. Yet for me, it was suddenly and frighteningly real.

I wondered how a recently successful, and apparently intelligent young woman could end up in this place. A few months ago I had been chasing my life dreams. A year ago I had been a project manager at a large corporation. I had a degree. This wasn’t what my life was supposed to be.

As it turned out, most of my fellow patients were far removed from stereotypical nutters themselves. We crazy folks have many experiences and talents, but none of them sufficient to keep us out of the ward. I was to meet mathematicians, artists, musicians, an admiral, and several versions of Jesus. Mostly people were disappointingly and comfortingly normal.

Passivity, pills, telly and paperwork.

Being a patient in a psychiatric ward was far from what I would have imagined, had I ever imagined such a thing for myself.

There were no padded rooms, no hunched orderlies in white coats. It was not the movies, it was a hospital. It even smelt like a hospital, but that odour of antiseptic was mingled with notes of sweat, urine and old shoes.

While the drama of Hollywood institutions was absent, so too were many things I expected and wanted. I expected to see a therapist. I expected counselling groups. I expected lots of help to work out what had happened to me. I expected to be able to talk about my past, maybe even plan for my future. I expected that staff would be there to help during emotional crises. I expected treatments that worked. None of these expectations were met.

Most people I meet who have never been to a psychiatric ward imagine that these same things would be provided. They are not. If I could characterise what is done in a psych ward in a few words, I would have to say passivity, pills, telly and paperwork.

I saw a psychiatrist once and sometimes twice a week. These meetings invariably made me feel like a bug under a microscope as I was asked obviously predetermined questions and many notes were made in my ever-growing file. I was given diagnostic labels and then I was given medication.

In ten psychiatric hospitalisations I never once saw a psychologist, therapist or counsellor. There was no group therapy. Although there was the occasional art or music therapy group which provided some distraction.

When I was new to the hospital I was alarmed by the way that I kept noticing nurses watching me and writing on clipboards. I felt increasingly paranoid about it until a fellow patent told me that these were called ‘obs’, that I was clearly on 15 minute obs, and that I should ‘act normal’ whenever I saw the nurses watch me. I wasn’t sure any more what normal was, but I did my best.

Still, it was hard not to jump when nurses would shine a torch into bedrooms at night to check on us. It was hard not to feel abandoned and scared when I felt desperately suicidal – but would have to wait at the nurses counter for 20 minutes while I could see them talking, laughing or even doing crosswords inside the glass office.

There were scary aspects to the hospital. I only got glimpses of most of them during my first admission, but over time I would discover them all intimately.

The ‘High Dependency Area’ where we were locked into a small, grotty common area and watched closely. Only plastic cutlery in here. Even the telly was behind old, scratched Perspex.

The seclusion room, not padded, but furnished with blank walls, a seat-less toilet and a rubber mattress. There was a tiny, steel reinforced window in the locked door.

The pristine suite where we got shock treatment.

The times when a group of nurses would physically ‘take down’ a patient, knocking them to the floor, forcibly inject them, and carry them off.

The first time I saw a ‘take down’ I watched in amazement. I had been aware of this young women trying to get attention from nurses in the office for what seemed like ages. She was crying, shaking, jiggling, calling out for a nurse, but no-one came. She got louder and louder, but still no-one came. And then she ran into the dining room, picked up a chair and threw it. The nurses came pouring out of the office at high speed, but it didn’t end well. It was a terrifying incident to watch and it all seemed so avoidable.

I worry that I sound too negative.

There were some amazing staff. People who went out of their way to listen and help. But in my experience they were notable for being the exception.

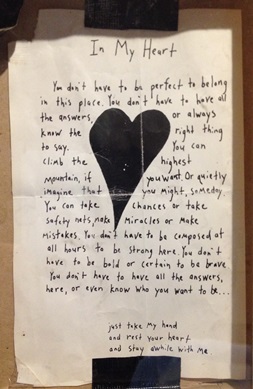

When I could get a nurse’s help during a crisis, for example, mostly I would be given fast-acting pills to take, usually Valium. But I remember once a nurse took me for a walk, taught me how to slow my breathing, and then listened to me. A remember an agency nurse who I only met once. She got me to lay down and talked me through a meditation about loving kindness. And I remember a student nurse who would sit with me for long periods and encourage me to talk. She gave me this poem that I still keep close to me.

Unexpected gifts in hospital.

Knowing how to spell the plural form of ‘Jesus’ is not required in many writing situations. But it is when you tell a story set in psychiatry.

One of the Jesuses (yes, this is the correct spelling, I checked) that I met while in hospital was especially memorable. I mentally called him ‘Post-It-Note-Jesus’. He would spend his days making whole cigarettes out of the collected ‘butties’ left on the ground by other patients. He would also make compassionate notes for the patients and staff, and stick them up for us in unexpected places. They were, naturally, always signed ‘Jesus’. For many of us with so little to do or hope for on the ward, a post-it-note from Jesus could be the highlight of a day.

‘You are loved – Jesus’. ‘You are a kind person – Jesus’. ‘You will get out of here – Jesus’. ‘Jesus loves you – Jesus.’

One afternoon I was sitting on the floor of the ward, huddled and rocking in a corner, and willing myself to disappear, when Post-It-Note-Jesus approached. He dropped down to the floor in a kind of majestic swoop and put something into my hand.

‘You look like you need some privacy,’ he said, smiled beatifically, then rose and drifted off. I looked at my hand. In it was a set of rosary beads and a pair of plastic sunglasses, with one lens missing.

I still have these items today, some fourteen years later. The real gift was not on the surface. Like so many of the gifts life brings us, they were ugly, cheap and provided no sun-protection. I was a lapsed Jew, so the rosary wasn’t quite to my taste. But this gift contained an acknowledgement of how dreadfully raw and exposed I felt, and it was a connection of pure humanity.

A complete stranger, a man struggling with his own madness and incarceration, had seen my inconsequential moment of desperate struggle, and he took creative action to help when no-one else did a thing.

I still think of Post-It-Note-Jesus with a smile; while psychiatrists decided he was mad, this wonderful man gave me his deepest beliefs, privacy for one eye, and a moment of grace. Thank you, Jesus.

The moments that stand out for me during my hundreds of days spent in psychiatric wards almost all come from other patients.

The roommate who eventually became a dear friend, who held my hand and told me where I was after every session of shock treatment. Even though the nurses told us touching was not permitted between patients.

The fellow patient who found me sobbing on the concrete courtyard ground and said nothing, but sat beside me and played her guitar.

The man who gave me a canvas of his own so I could paint on something other than kindergarten quality paper.

The people who helped me out with practical ways to get by, like spare clothes, and pens.

The man who sat next to me in the art room, looked at my drawing, and told me that he saw the same things.

The fabulous folks who were utterly inappropriate and smuggled in coffee, cigarettes and vodka, and shared their windfalls.

And the countless patients who shared their own ways of coping, surviving and not losing hope.

They called us consumers, not that we ever really got choice about the services we consumed.

I discovered the consumer/survivor/ex-patient movement in a psych ward. I discovered that the people who made the biggest difference for me were those who had travelled a similar path, and could tell me about the winds and twists and potholes. I discovered that the consumer/survivor/ex-patient movement in mental health is a great human rights movement with centuries of history, and still much to do in its future.

And, eventually, I would discover that the consumer movement held the keys to my own recovery.

About this article.

This is an extract from my madness memoir, still in development.

It has become a tradition, almost a rite of passage, for those of us who emerge from years as ‘consumers’ in the psychiatric system to put our stories to paper.

There are many personal and systemic reasons for recovered mad folks to write their stories. There is of course a certain catharsis to the process of writing. For us as writers of our lives it is a chance to reflect, assimilate, reconsider, grieve and celebrate our journey. I have found great personal transformative benefits in writing.

It is also about reclaiming our power. When we are ‘consumers’ it is always other people who tell our stories – in case notes and case meetings, reports and statistics and research analyses. It is rare that we get to be the author of our own stories and give our own perspectives – after all, we are mad, our strange perspectives are the very reason we have entered the system! What could we have to say that is relevant? I will tell my story. Others can judge its relevance.

First published 10 June, 2015. Re-published with minor edits, 25 April 2019.

Comments