What happened when compassion replaced clinical objectivity, and creativity replaced compliance.

One morning in 2009 I was sitting in the psych ward, working on a plan to kill myself.

I was made an involuntary psychiatric patient following a rather extreme type of self-harm, even for me. My home had been rushed by police, ambulance officers and a psychiatric crisis assessment team, and I’d been carted off to the ED, and then the psych ward.

I was being plagued by the voice in my head, who I called ‘The Judge’. I thought there was a beast who lived inside me, I thought I was evil and I thought that I had to be destroyed. I felt trapped in an inescapable and tormenting madness.

This was the morning after a meeting with the consultant psychiatrist, and what she’d said had stripped away my last vestiges of fight. She had changed my diagnoses, but not my treatment.

Apparently the same treatment would apply no matter what labels I had. She’d told me that getting control of my symptoms and getting back to work was more important than anything else – even more important than my struggle to find a way to stop hating myself.

She had listened to me talk about trying to make sense of my childhood traumas, but then told me that I must forget my past and stop any therapy to explore my childhood trauma.

You can’t cope with doing this, Indigo, she’d told me in a compassionate-sounding voice. And then she went further, contacting my private psychologist and directing him to stop talking to me about my childhood. I did not even attempt to argue with her, because I knew that would only make things worse.

No matter what I do, no matter how I try, I always end up in hell, I was thinking to myself. There is no escape from the beast inside me or from the cruelty of others. She has not heard. She has not understood. Everything in this system is designed to trap and trick me deeper into hell.

I had given up.

You can’t win an argument with a psychiatrist, I decided, not ever. If you try, they just say you have no insight and put you on a treatment order.

I knew this doctor was a good person and she hadn’t meant to hurt me. I knew she wasn’t cruel. I knew she wasn’t stupid. Despite the fact that what she’d just done felt exactly like how a cruel person would stupidly destroy my hope. She was as trapped in this system as I was, but she got a huge income and I got despair.

Immediately after meeting with her I concluded that death was my only remaining option. I was working on a suicide plan, when out of the blue I got a phone call from a colleague and friend.

She told me that Andrew (not his real name), someone I knew and respected from the UK Hearing Voices Movement, had flown into Australia that day. When he heard I was in the hospital, Andrew had insisted on coming out to visit me straight away – and they were on their way now.

Andrew is a mental health worker with his own lived experience. I was surprised and honored that he wanted to see me. This was a tiny little light that drew me to rush off to my room and get out of my crumpled mint green hospital pyjamas before he arrived.

The extraordinary impact of using compassion and creativity

Andrew arrived at the hospital and asked the nurses to give us a private room to talk in. It was the same room the psychiatrist met me in, and yet it wasn’t.

The cheap tub chairs held the same rigid shape. The glass walls remained solid in their frosty demeanor. The carpet sat stiff and tight in its unremarkable practicality.

And yet the room no longer felt like a cold lab. I did not feel like I was a disturbing and passive subject under examination by scientists. I did not feel like others were trying to fix the bits of me that they thought were broken. I did not feel powerless.

Instead, this room became a gallery that wanted to explore the full picture. It became a recording studio that heard me in hi-fidelity. It became a safe space that was warmed with genuine care. It became a library where wisdom was shared and explored and equal. Spaces matter, but people can make all the difference.

Andrew sat next to me, not across from me. He didn’t make notes in his own file (he didn’t have a file), but we wrote things together in my own journal. Unlike the doctors, Andrew didn’t ask me questions that were obviously from a predetermined list. Instead, he followed the direction that I set, and my story and pain was the guide. Andrew didn’t shut down my weirdness, instead he wanted to know more about it. He knew that my experiences mattered to me, and that the meaning would come from me rather than from a diagnostic manual.

When I mentioned my drawings in my journal, Andrew didn’t tell me to put it down and focus on his question, but instead he asked to see it and hear more. When I asked him questions, Andrew didn’t give me answers. Instead we each shared ideas that we unpacked together.

There was never that slight expression change that would sneak through on the doctor’s faces, when you just know they think you’re raving bonkers, but they try to hide it. We can always see that look.

During my two-hour conversation with Andrew I felt safe and heard. Even more than that, I felt like we were partners, working together to explore a complex and scary territory.

Together, in my journal, Andrew and I drew up a map of the different parts of me. We looked at the Judge voice that had been tormenting me, but we looked at him as just one part amongst the many parts that make up my whole. I realised that the Judge had lots of power over all the other parts, and I could see that this power was way out of balance. That’s why I was here, in this hospital.

Andrew asked me about his name, ‘The Judge’. This question helped me to see that a part of his purpose was obvious in his name: he was a critic, he was the holder of my moral values, and he held me to account against these values with a savage and unwavering focus. The Judge’s view was pretty much that I must be entirely and absolutely good and pure, or I must die. Andrew told me that almost everyone has a critic part of themselves, and sometimes they can be very strong.

As I sat there, thinking about how terrifying and brutal the Judge could be, Andrew shared his own reflection:

It sounds like the Judge has a lot of responsibility. I wonder if he might be lonely.

Wow.

Seriously, wow.

This was so very human. So kind. So unlike anything I had ever thought about the judge before. So unlike anything anyone had ever said to me before. And certainly not the kind of thing a psychiatrist might say. I was on a different planet.

Loneliness and responsibility. Not so different to how I have felt myself many times in life. When you feel responsible for a lot, and you feel alone too, it can be overwhelming. It can be hard to hold onto compassion.

Andrew’s simple but insightful little comment instantly took some sting out of my experience of the Judge. It helped me to see him as more human and fallible. It made me think, for the first time, about how the Judge might feel, instead of how I feel.

I mean, I knew that my voice and I were one and the same, but still, we were different too. The Judge had a job to do, he found it hard, and he was alone in his struggle. Maybe that was part of why he was so harsh?

A new idea began, only just, to grow in me. The idea of listening to the Judge with compassion, rather than with fear. Over time this idea would open up many new avenues in my recovery.

Andrew had noted earlier that I also had a part of me that was a ‘helper’. I reflected that mostly my helper cared about other people, not me. And Andrew wondered if I could ask my helper part to help me to dialogue with the Judge. We explored some questions that my helper self could ask the Judge. Questions that would help me to better understand the Judge, like why he was there, and what he really wanted. This was also to lead to many breakthroughs for me, over time.

We explored some of my disowned selves, like ‘the vulnerable child’, ‘the nurturer’, ‘the beast’, and ‘mindful me’. These were much harder to talk about. I felt uncomfortable, awkward. I didn’t like any of those parts, it was weird to acknowledge that they were there at all. And talking about the Beast was frightening. This was the disgusting, evil part of me. This part was why the Judge wanted me to be punished or to die.

Andrew made a gentle suggestion that the ‘Beast’ might be able to transform into the ‘Lover’ if I could find a way to give it some space and time.

At the time it seemed like an astonishing suggestion. I thought perhaps Andrew was confused. It made no sense to me why he would say such a thing. A satanic beast turning into something to do with love? How? What did he mean? The very idea seemed both nonsensical and somehow perverted.

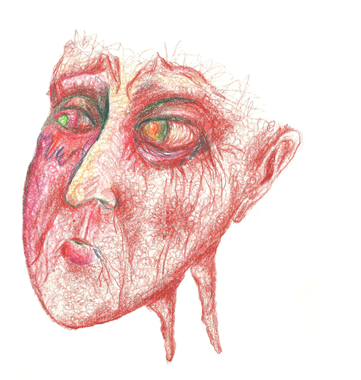

Of course, I look back and it’s obvious. I didn’t name any type of sexual or loving self. It’s such a fundamental thing that was wholly missing from my map of me, from my life. But I had told Andrew about the sexual assault and abduction in my childhood, and then I had shown him my drawing of the Beast.

I guess that’s a feature of madness. The things that torment us become so large and loud that they lose their shape and substance. We can’t see what they are anymore. We hear the screaming of truth, but the words become unintelligible, another language from another, strange place where pain has distorted reality.

Andrew and I explored gentle ways to transform the Beast part of me, to let it find its place as a primary self, rather than something I disowned and wanted to destroy. He suggested that I draw on my mindful self, that I invite my vulnerable child out to play, that I write letters to it.

This has been a journey that has taken years, but today I actually do think of this part of me as my ‘Injured Lover’, not as a ‘Beast’.

I even have a painting that shows the transformation of this part of me, from something terrifying and evil into something beautiful and hurt.

In my painting, the injured lover is slowly growing, like a eucalyptus seed after the ravages of a bushfire. I come back to this painting and rework it every year or so. My injured lover is still injured, probably always will be. And it’s not really a primary self yet. I still forget about it often, and sometimes I wish it wasn’t there at all. But it is, and I know that caring for this part of me is central part of my healing. This work reminds the Judge that there is no beast, no evil, just a vulnerable and hurt lover that needs our care. This keeps me together, often.

And finally, came the penultimate creative, healing idea from Andrew. This one was a humdinger.

Andrew asked me something strange:

I wonder if there is anyone who could job-share with the judge? You know, so he’s not so alone? Could you create another voice to work with the Judge?

I said I’d think about it. Frankly, I thought it was whacky.

But I respected Andrew so much that I had to give it some thought. Plus, it was so whacky, and so subversive, so utterly the opposite of what anyone had ever suggested, so obviously something that I knew would make my psychiatrist immediately alarmed, that it just kind of charmed me. To be here, stuck in a psych ward, hearing voices, and contemplating creating a new voice to help me. Bloody nuts. I was going to try it.

After Andrew left I felt energised. I had work to do. Secret Recovery Business. I dismantled the suicide plan that I’d previously put into action. I made a commitment to life.

The task of creating a new voice

All night I thought about creating a pal for the judge. I needed some relief from him, and the more I thought about it, the more it made sense to have at least two judges to share the load, rather than one tired, furious old man.

But who could this new voice be?

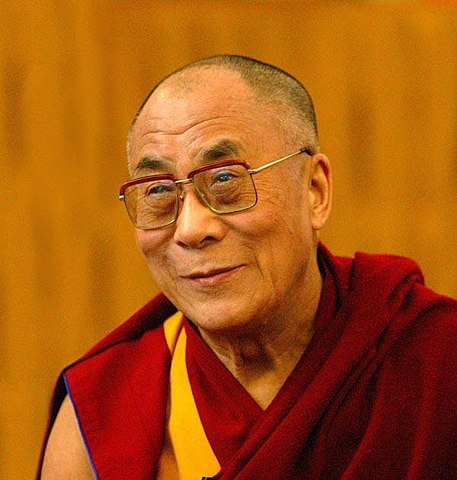

Initially I wanted to create the Dalai Lama as a new voice. I always thought he seemed to radiate peace and acceptance, he seemed a natural counter-balance to the Judge. But I didn’t want another man in my head.

I tossed and turned, trying to think of a woman who represents wisdom and kindness. Who I could trust to make the right decision. Who was innately good.

And finally it came to me.

I know, dear reader, that this will sound inordinately cheesy and may diminish me in your eyes. I hope you understand.

It was Mrs Ingalls. The mother from my favourite childhood TV show, ‘Little House on the Prairie’. Look, I know she is not cool. But I was not in a cool place; I was losing my mind and trying to stay alive. And Mrs Ingalls, well, she made me feel safe. Still does, actually. So stick with me. Mrs Ingalls is da bomb.

Like most kids, television gave me another world to escape into. For a time, my favourite place to escape was into the world of Little House on the Prairie. This western family drama was a staple for heaps of 70s kids (it was either this or The Waltons), and it would probably be laughed off the screens today.

Its morals were simple, its characters were stereotypes and everything always worked out in the end. It was nothing like my real life, or anyone else’s, and I loved it to bits.

I was torn between childish adoration of both sisters in the Ingalls family: Mary and Laura. I aspired to Mary’s kind heart and studious commitment, I really did, but ultimately I would guiltily identify more with younger sister Laura’s independent spirit and wild adventures. Probably just like every other kid glued to the show.

Sometimes, when I was little, I wished that I was part of the Ingalls family, even with their dirt floor and worn out clothes. Mrs Ingalls was gentle and wise, Charles Ingalls was strong and protective, and they were always there for each other. Every episode hit this little family with a new hardship, and every episode they battled their way out of it, together. Every battle gave us a lesson about courage, or tenacity, or sacrifice, or kindness.

Those of us who grew up with this little gem of a show may remember a particular stand out episode. Mrs Ingalls was at the general store, planning to buy some practical, hard-wearing and cheap cotton for a new Sunday dress. But the obnoxious, loud-mouthed Mrs Olsen, proprietress of the general store, and villain that we all loved to hate, was on form. She was so utterly patronising to Mrs Ingalls about what was suitable for a woman of her means that Mrs Ingalls gave in to her pride, and bought a length of fancy fabric far beyond the family budget. It was out of character for her. In this little world, it was shocking. Charles, her husband, was of course forgiving, but you could see the strain pulling at the edge of his chiselled manly features. See him thinking about how much more timber he’d have to mill and how many more fields he’d have to plant, just to pay for this piece of pretty nonsense.

Late one night, as Mrs Ingalls stitched away at her inappropriate floral blue dress by the light of her oil lamp, and everyone else slumbered in their off-kilter handmade beds, we saw her realise what she had done. How pride had made her forget her family. She stayed up all night sewing, while we listened to dramatic music, and when the girls got up the next morning and climbed down the ladder from their attic bedroom, lo and behold: two little dresses had been sewn in the night, one each for Laura and Mary. They would have the prettiest dresses of all the girls in the township. Mrs Ingalls found a way to turn her error of judgement into a gift for her girls. How could you not adore Caroline Ingalls?

This was the woman I thought could help save me. In many ways she was the opposite of everything that the Judge did and said. But, like the Judge, she had strong morals and she always found a way out of any problem. She was perfect.

The next day I grabbed a sheet of bright yellow cardboard from the art room, and folded it in two, lengthwise. On the left side I wrote: ‘The Judge’. On the right I wrote ‘Mrs Ingalls’. And for the next two days it went with me everywhere. Folded and unfolded, again and again. And every time the Judge made a comment, pronouncement or order, I would write it down in his column. And then I would ask Mrs Ingalls for her opinion, and write that down too.

I didn’t hear Mrs Ingalls in the way that I heard the Judge. I didn’t actually create a new voice, not really. But I knew, instinctively and instantly, what her response would be. I grew up with that show, and Mrs Ingalls was ingrained into my inner child.

So, the Judge would say something like, filthy whore, you have to die. And then Mrs Ingalls would say, My darling Indigo, these are very hard words, and I don’t believe them and I won’t use them. We all have goodness in us. You must live, and focus on your goodness.

It was a strange experience, but it gave me strength. I didn’t tell my doctors about it though. Admitting to psychiatrists that one has invented a new voice in order to make sense of an existing voice is not a helpful way to get discharged. Well, not yet, anyway.

In a way it did help me get discharged, even though no-one else knew it. Because it helped me to start relating to the Judge in a wholly different, and kinder way. Creating an internal Mrs Ingalls awakened the compassionate part of myself. It didn’t stop the Judge. It didn’t change the content of what he said, or how he said it. But it began to change how I felt about what the Judge said. It began to change my responses, too.

One afternoon I got leave to go and see my private psychologist. I talked to him about how I was trying to find more compassion for my voice, without too much detail about the process. So he loaned me a book by Thich Nhat Hanh, called Anger: Wisdom for cooling the flames.

This book was another revelation. I didn’t agree with all of it. And some days the calm, poetic beauty of Thich Nhat Hanh’s writing made me want to punch his lights out (I was not, obviously, in a calm, poetic or beautiful place or state of mind). But there was an innate wisdom in his words. His writing gave me extra tools to find compassion for the Judge.

I began to visualize the Judge as an angry, screaming baby in distress. And I would hold my hand to my forehead, the way that a mother does to a sick child, the way that Mrs Ingalls would, and whisper to the Judge, I love you, I hear you, I know you are hurting, I know you only want me to be good.

Getting free of hospital and onto my healing path

Between the compassionate creativity of a peer who worked with me rather than on me, the kind words of an imaginary woman from late nineteenth century midwest America, and the compassionate actions inspired by the words of an exiled Vietnamese Buddhist monk poet, I found ways to stop hurting myself.

I found the fragile edge of compassion and clutched onto it with my fingernails. I didn’t really feel it truly. It was just a tiny beginning. A single ice cube, tottering in a sea of wild, storming lava. But it was enough.

It was enough that I stopped self-harming. It was enough that I made a decision to keep going on my healing journey, but with some new strategies. It was enough that I made a decision to get out of this hospital hell so I could find new people who would understand and work with me to help understand my trauma. It was enough for me to carefully work out what I had to do in order to get discharged, and then do it.

I stopped complaining about my diagnoses and pills. I kept a straight face while I said that I thought the pills must be making things clearer for me. I told the psychiatrist that, on reflection, she was right. I wanted to get back to work, to put this business behind me. She was right to say that I shouldn’t talk about my past any more. I sat down in the art room and wrote up a fake recovery plan, and filled it with loads of stuff that I knew the psychiatrist would approve of. I will take up some of my old hobbies to keep busy. I will distract myself when I think of the past. I will ask my therapist to do a refresher with me on coping skills. I will put a poster on my fridge to remind me to take my pills. I will stay with friends or family once a week so I don’t get isolated. I will take things slowly. Actually, I did do the last two things.

I showed the psychiatrist and she beamed. I think my grade moved from a ‘C’ to a ‘B+’. We are making great progress, Indigo. I think we can start to plan your discharge.

In less than a week I had a trial stay at home without incident. Then I was out of hospital. A few outreach visits from a nurse where I was careful to say things that would ‘demonstrate insight’. I made sure to ask for advice about how to remember to take my pills because ‘sometimes I’m forgetful’. For some reason, services seem to be much less controlling of us when we act less competent, show less confidence, and ask for their help.

Then, when I was free of it all, one of the first things I did was to find myself a specialist sexual assault counsellor, at a service called CASA (Centres Against Sexual Assault). It was a free service, and it was extraordinary. Full of feminists and freedom and creative compassion and almost the complete opposite of a psychiatric ward. The second was to slowly reduce and then stop taking the antipsychotic pills. I needed to be able to think and to feel if I was going to do this trauma work.

My actions were the complete opposite of the psychiatrist’s medical advice. And even though I had been officially nuts, it turned out that I was still right. This did indeed become a path of healing for me, and I never went back to hospital or a psychiatrist again.

I will be forever grateful for that visit from Andrew. The psychiatric system had failed me, utterly. It had failed to listen to what mattered to me. It had failed to even try and see my experience through my eyes. It had failed in being trauma-informed, recovery-oriented or person-centred. It had tried to control me and limit me and drug me. It had forced my therapist to stop working with me on what I wanted. But I was lucky. I found someone who heard me and partnered with me. Who offered compassion instead of clinical objectivity, and encouraged creativity instead of compliance.

There is a part of my story that still gnaws at me. My healing and freedom were a matter of luck, not design. Almost no-one gets the kind of opportunity that I was given that day. And almost every day of my life, I think about all the thousands of people in psychiatric services who will never get a visit from someone like Andrew, who will never get the kind of compassion and creativity that enabled me to find my hope, my freedom and my healing path. People with suicide plans underway, like I was. What will happen to them? This is why I continue to work as an activist and advocate for change, and to tell my stories in places like this blog.

Originally published 13 March, 2016, re-published 28 April 2019.

Want to read more?

Check out more blog articles and recovery resources or subscribe to my emails.

Comments